Meg Duguid Explores The Intersection Of Performance, Object-Making, And Optimism

Photo: Meg Duguid in her element, reimagining art through the interplay of performance, innovation, and a visionary eye for storytelling. Meg Duguid, 2012 photo by Catie Olson

Blurring Boundaries Between Art And Life

Meg Duguid delves into her process-oriented practice, blending performance, film, and installation, while exploring themes of optimism, storytelling, and the endless cycle of creation and re-creation.

Meg Duguid is nothing short of a creative force. Her multifaceted practice traverses the boundaries of performance, visual art, and object-making, constructing a world where imagination and rigor collide in extraordinary ways. A visionary artist and thoughtful arts administrator, Duguid is deeply embedded within the fabric of Chicago’s cultural community as both a creator and advocate. From her captivating performances to her ambitious curations and groundbreaking public projects, Duguid’s career is a testament to the power of art as both a personal and communal act of transformation. Her vibrant intellect and innovative spirit have made her a fixture in esteemed venues across the globe, inspiring audiences with works that transcend traditional artistic categories.

In this issue, we’re thrilled to feature an intimate conversation with Duguid, exploring the alchemy of her process and the thematic heart of her oeuvre. Through projects like the mesmerizing Tramp Project, she challenges conventional narratives and redefines how art can navigate and reflect the complexities of contemporary existence. Meg’s unique fusion of performance, film, and installation allows her art to continuously evolve—each piece is a kaleidoscope of creativity, inviting us to imagine, question, and feel. It is with immense pride that we share her insights, her relentless innovation, and her unwavering optimism, which serve as guiding lights in the ever-changing landscape of the arts.

Meg Duguid is a brilliant artist whose boundary-defying practice reshapes how we perceive performance, storytelling, and collective creativity.

How do you envision the role of the studio in your process, especially as a space that merges object-making with performance?

My studio is where I am, and it is a site that is ever-changing. It can be in my own body, in a public park, in a suitcase, at a chop saw, or at my small drawing table and computer. The idea that a studio practice should function alongside a performative practice doesn’t seem alien to me. Performance art came out of visual practice; it was an extension of visual composition into action and movement. I think the traditional media has always been there for performance in both the genesis and the documentation of it, so really, I am just treading its material history.

“My studio is where I am, and it is a site that is ever-changing.” – Meg Duguid

Can you elaborate on how you approach reusing, repurposing, or modifying pieces across different contexts, like performances, installations, and exhibitions?

There are objects and materials that I like. These things constantly find their way into my practice—suitcases, mustaches, bubbles, bubble wrap, ladders, and suits made of Tyvek.

You mention blending formal qualities of visual media with the raw essence of performance art. How do you achieve this balance in your work?

I have been working on a project that balances this dichotomy called the Tramp Project. Throughout the Tramp Project, I am generating a set that is a platform for a series of performances. The result of those performances is a fully edited cinema experience, a series of objects and sets, and a series of production stills, all of which can be interchanged in various exhibitions and screenings that continue to loop from performance to documentation and back to performance again.

“Optimism is something that should be tended to and nurtured in holistic ways.” – Meg Duguid

In essence, the performance is the shooting of the film, the film is the documentation of the performance that is screened to an audience while an experimental band plays a live score, the live score is then edited into the film, which is then rescreened to a new audience . . .

Not only does the project reenvision the Tramp as female, but the narrative is still timely. It’s a post-apocalyptic romp where a super-atomic bomb is dropped, leaving seemingly just one survivor, the Tramp. As the picture unfolds, it is clear that others have survived and are coalescing around two separate and completely different communities—the Tramp’s community, which is rebuilding a community by hand, and the community of scientists who created the technology for the bomb and who restore their technology and mechanized existence. For a majority of the film, the communities are unaware of each other. Eventually, the Tramp’s community (but not the Tramp) is lured to the scientists’ way of life. In the end, the Tramp, alone, walks from this new world into the sunset.

How does the concept of an “economy of optimism” shape or influence the themes and methods in your art?

I believe that optimism must be carefully managed. Optimism is something that should be tended to and nurtured in holistic ways. There is a glory to making, deconstructing, and making again. As I am making, I am also divining what comes next and pulling it apart to do it all again. I find comfort and optimism in not having a total end point.

Could you describe a recent piece that exemplifies how a single work has evolved across multiple iterations or mediums?

In the case of the Tramp Project, I started by dissecting the film’s script into stop animations as a storyboard for the entire set of performances (I see stop animation as a performance for the camera). Those animations in turn not only have been used to lay out work for projects like Production of Atomic Credits and Parade for a Nuclear Bomb. They also are used for creating a set piece and exhibitions called Supercomputer, which consisted of all the storyboard animations I created to map out how to make this project, displayed on 16 old monitors; this installation will later be re-installed in the film in the scientists’ underground lab as a part of the lab’s massive computer that tells the scientists what to do. Each step is both a final stop on the way to creating the film and a draft which I can remake over again as many times as I need to.

Since your work is deeply process-oriented, what excites you most about the future potential for this cycle of creation and re-creation?

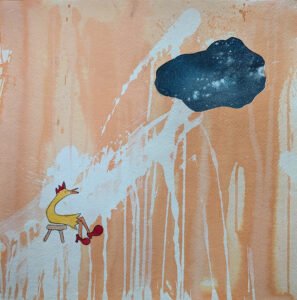

During the pandemic I was unable to work in my studio due to childcare and life. I am in the process of discovering how I have changed. So, I have been working on a series of drawings featuring a rubber chicken in high heels along with animations that are me performing for myself to understand where my artistic DNA lies now. I am also getting back to the Tramp Project. I am excited to revisit the storyboard again and to rebuild the supercomputer with more wires and inputs as well as utilizing projection.

EDITOR’S NOTE

Meg Duguid’s Rubber Chicken Series is a quirky yet profound exploration of absurdity and identity. Rendered in gouache, ink, and graphite, this 2023 piece showcases a playful yet provocative aesthetic. The brightly crowned rubber chicken perched on a stool, clad in high heels, exudes whimsy and surreal charm. The textured orange and white background juxtaposed with a mysterious cloud-like shape invites viewers to reflect on themes of curiosity and existential wonder. Duguid skillfully balances humor and abstraction, crafting a scene that feels dreamlike and introspective. Her imaginative reimagining of ordinary objects elevates them into vibrant, thought-provoking storytelling elements.